Capital Partners: Understand Your Rights as an LP Before You Invest

Capital Partners: Understand Your Rights as an LP Before You Invest

When you invest as limited partner in real estate partnerships with capital partners providing funding while general partners handle operations, you’re entering legally binding relationships where your rights, protections, and return priorities get defined through operating agreements governing partnerships. Many passive investors commit substantial capital—often $50,000-$500,000 per deal—without thoroughly understanding their actual rights as limited partners, the circumstances under which they might lose capital, how distributions get prioritized, or what recourse exists when partnerships underperform or sponsors act inappropriately.

The power dynamic in capital partners relationships naturally favors general partners who control daily operations, property management decisions, financial reporting, and exit timing. As limited partner, you’re investing money but surrendering operational control, trusting that sponsors will act in your best interests while managing your capital responsibly. This trust-based structure works beautifully when capital partners operate ethically and competently, but creates vulnerability when sponsors make poor decisions, engage in self-dealing, or simply lack the expertise they claimed when raising capital.

Understanding your rights as limited partner before committing capital—not after problems emerge—represents the difference between protected investments with appropriate recourse mechanisms versus powerless positions where you watch helplessly as sponsors destroy your wealth through incompetence or malfeasance. This guide examines capital partners structures, your specific rights as LP investor, critical protections to demand before investing, red flags signaling problematic partnerships, and steps to take when relationships deteriorate beyond repair.

Key Summary

This comprehensive guide clarifies limited partner rights in capital partners relationships, helping passive investors protect their interests before committing capital to real estate partnerships.

In this guide:

- How capital partners structures define roles, responsibilities, and decision-making authority between general and limited partners (partnership legal structures)

- Your specific rights as limited partner including voting rights, removal provisions, and distribution priorities (LP investor protections)

- Critical operating agreement provisions that protect limited partners or leave them vulnerable to sponsor abuse (partnership agreement essentials)

- Red flags indicating problematic capital partners relationships and when to walk away from deals despite attractive projected returns (sponsor due diligence)

[IMAGE 1]

Understanding Capital Partners Relationships: GP and LP Roles Defined

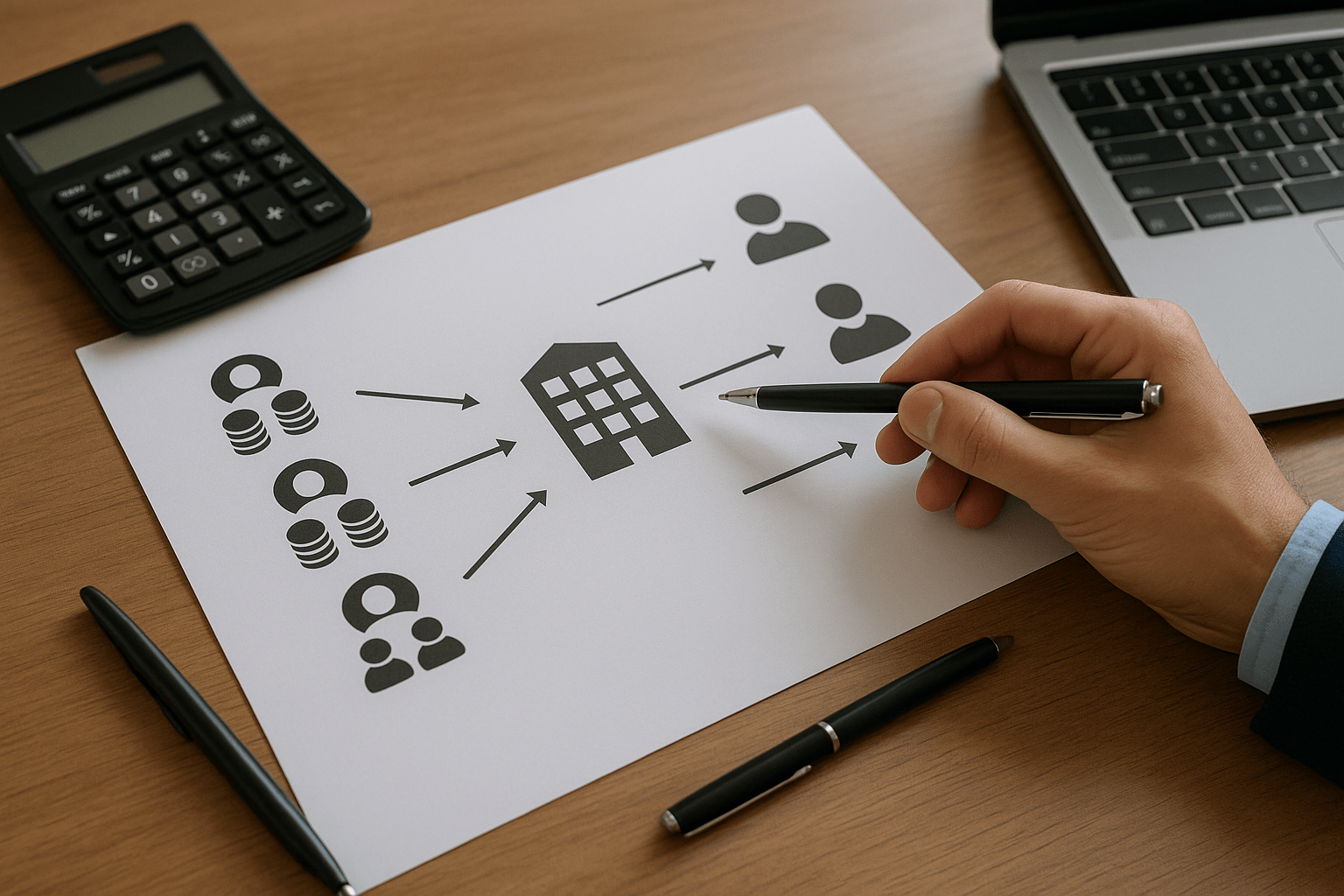

Capital partners relationships in real estate investments organize as partnerships or limited liability companies where distinct parties contribute different resources—capital versus expertise and operational management—sharing both risks and returns according to negotiated structures defined in governing documents. Understanding these fundamental role distinctions clarifies what you’re actually agreeing to when becoming limited partner in capital partners deals.

General partners (GPs) or sponsors serve as active managers controlling all operational aspects of partnership investments. These capital partners source investment opportunities, conduct due diligence, negotiate acquisitions, secure financing, oversee property management, coordinate improvements or repositioning, handle accounting and reporting, and ultimately orchestrate exits through property sales or refinancing. General partners typically contribute modest capital proportions (5-15% of total equity) while providing substantial sweat equity through time, expertise, relationships, and operational execution. Their compensation comes through multiple fee streams—acquisition fees, asset management fees, disposition fees—plus disproportionate profit sharing (promoted interests or carried interest) rewarding superior performance beyond minimum return thresholds.

Limited partners (LPs) provide most investment capital (85-95% of total equity typically) while maintaining completely passive roles with no operational responsibilities, management duties, or daily decision-making authority. As limited partner, you’re essentially a silent investor—providing money, receiving periodic distributions, and participating in major decisions (if operating agreements grant you those rights), but delegating all operational authority to general partners. Your liability is limited to invested capital amounts—you can’t lose more than you invest even if partnerships face catastrophic losses or liabilities. In exchange for this limited liability and passive role, limited partners typically receive priority distributions through preferred returns before general partners participate in cash flow, plus majority profit sharing when properties ultimately sell.

Alignment of interests between general and limited partners determines whether capital partners relationships function harmoniously or devolve into conflicts. Well-structured partnerships align both parties toward common objectives: limited partners want strong returns on invested capital while general partners want compensation reflecting their efforts plus equity upside from superior performance. Problems arise when structures misalign interests—perhaps general partners earn substantial fees regardless of performance, creating incentives to acquire properties and collect fees even when deals won’t generate strong limited partner returns. Or when general partners contribute zero personal capital, insulating themselves from downside losses limited partners suffer. Evaluate whether proposed structures truly align everyone’s incentives before committing capital.

Fiduciary duties require general partners to act in partnership’s best interests, not just their personal interests, creating legal obligations to manage capital responsibly and avoid self-dealing transactions benefiting sponsors at limited partners’ expense. These duties include loyalty (avoiding conflicts of interest), care (managing investments competently), disclosure (providing complete honest information), and good faith dealing (acting honestly in partnership matters). However, operating agreements can modify or even eliminate certain fiduciary duties—a critical reason to review these documents carefully rather than assuming default legal protections always apply. Some sponsors negotiate away fiduciary obligations, creating legal permission for self-interested behavior harming limited partners.

Capital partners in the context of limited partnerships represent all equity investors collectively—both general and limited partners comprise the ownership group. However, the term “capital partners” sometimes refers specifically to limited partners providing capital, distinguishing them from operating partners (general partners) providing sweat equity. Understanding these terminology variations prevents confusion when reviewing offering documents or operating agreements referencing “capital partners” or “equity partners” in different contexts.

Entity structures for capital partners relationships typically use limited liability companies (LLCs) or limited partnerships (LPs) providing liability protection to all parties. LLCs offer operational flexibility with simple management structures and favorable tax treatment through pass-through income taxation. Limited partnerships provide more formal structures with clear distinctions between general partners (unlimited liability) and limited partners (limited liability), though general partners usually form LLC entities holding their GP interests, effectively creating limited liability even for operators. The specific entity type matters less than ensuring proper formation, adequate capitalization, appropriate insurance coverage, and clear operating agreements defining everyone’s rights and obligations.

Tax treatment of capital partners structures provides pass-through taxation where partnership income, gains, losses, and deductions flow through to individual partners’ tax returns rather than facing entity-level taxation. Each partner receives K-1 forms annually reporting their proportional shares of partnership financial activity for inclusion on personal returns. This treatment avoids double taxation (entity and individual levels) but creates complexity when partnerships operate across multiple states or generate varied income types. Limited partners benefit from depreciation deductions potentially creating paper losses offsetting other passive income, though passive activity loss rules limit deductions’ usefulness for many investors without substantial passive income from other sources.

Your Rights as Limited Partner: What You Can and Cannot Control

Understanding your actual rights as limited partner versus what you might assume protects you from unpleasant surprises when conflicts arise or when you want influence over decisions affecting your invested capital. Limited partners possess both more rights than many general partners would prefer and fewer rights than many limited partners assume—knowing precisely where you stand prevents unrealistic expectations.

Voting rights on major decisions represent your most important control mechanism as limited partner. Operating agreements typically reserve certain “major decisions” requiring limited partner approval—usually defined as actions needing approval from holders of 51%, 67%, or 75% of limited partner interests. These major decisions commonly include selling properties outside normal business plan timing, refinancing significantly, removing general partners, dissolving partnerships, admitting new general partners, amending operating agreements substantially, or making fundamental business strategy changes. However, what constitutes “major decisions” varies dramatically across deals—some operating agreements grant limited partners approval rights over numerous decisions while others restrict your rights to only the most fundamental partnership changes.

Removal rights allowing limited partners to replace general partners for cause (fraud, gross negligence, bankruptcy, criminal convictions, or material operating agreement breaches) provide ultimate protection against truly problematic sponsors. However, removal provisions vary widely—some require only simple majority LP votes while others demand 75-80% supermajorities making removal practically impossible. Additionally, removal “for cause” creates high bars: proving fraud or gross negligence requires substantial evidence, merely disagreeing with sponsor decisions or experiencing underperformance typically doesn’t constitute removable cause. Even with removal rights, expect legal battles if actually attempting removal—sponsors rarely acquiesce gracefully to removal efforts.

Information rights entitle you to regular financial statements, property performance reports, and updates on business plan execution. Strong operating agreements mandate quarterly detailed financial reporting—profit and loss statements, balance sheets, cash flow statements, rent rolls, occupancy rates, and capital expenditure summaries. Weaker agreements might provide only annual reporting or cursory updates without detailed financials. Beyond scheduled reports, limited partners should possess rights to inspect books and records upon reasonable notice, ensuring access to complete financial information if quarterly reports raise questions. Without contractual information rights, you’re completely dependent on sponsor voluntarily providing updates—problematic sponsors can hide poor performance or self-dealing by simply not reporting comprehensively.

Distribution rights define priority and timing of cash flow from operations and eventual property sales. Typical waterfall structures provide limited partners with preferred returns (6-8% annually) receiving first priority before general partners participate in distributions. After limited partners achieve preferred returns, additional cash flow might split 80/20 (LP/GP) until limited partners reach cumulative return thresholds (perhaps 12-15%), with remaining distributions splitting 70/30 or 60/40. Upon property sales, proceeds first return invested capital to all partners, then distribute according to waterfall provisions. However, you have no absolute right to distributions—operating agreements typically make distributions discretionary based on cash availability and capital reserve needs, allowing sponsors to retain cash for property needs rather than distributing everything immediately to investors.

Capital call limitations protect you from unlimited funding requests beyond initial investments. Some operating agreements prohibit capital calls entirely—if properties need unexpected capital, sponsors must secure outside financing or inject personal funds. Others permit limited capital calls (perhaps 10-20% of initial investments) under specific circumstances like major repairs or opportunity purchases. The weakest agreements allow unlimited capital calls with your choice being contribute proportionally or suffer dilution of ownership percentages. Understand capital call provisions before investing—can you fund potential calls if requested, or would unexpected capital demands create financial hardship?

Transfer restrictions typically prohibit limited partners from selling partnership interests without sponsor approval, creating illiquidity until partnerships terminate through property sales. Some operating agreements include rights of first refusal where other limited partners or sponsors can match outside offers before you sell to third parties. Others prohibit transfers entirely except to family trusts or under specific hardship circumstances with sponsor consent. A few create secondary markets facilitating LP interest sales between sophisticated investors, though these remain rare. Accept that capital partners investments are illiquid for full hold periods—you’re unlikely to exit early except by selling interests at substantial discounts to fair values (if transfers are even permitted).

Liability limitations through limited partner status protect you from personal liability beyond invested capital. Unlike general partners who face potential personal liability for partnership obligations, limited partners risk only their investments. However, you can lose limited liability protection by participating in management, exercising control beyond rights granted in operating agreements, or acting as general partner in fact even without formal designation. Maintain your passive limited partner status—don’t involve yourself in daily operations, management decisions, or actions suggesting you’re acting as general partner regardless of title. Stepping outside passive investor role risks personal liability exposure defeating the entire point of limited partnership structure.

Inspection rights allowing access to properties, books, and records upon reasonable notice provide transparency ensuring sponsors operate appropriately. Strong operating agreements grant inspection rights while weaker ones might restrict or eliminate them. Even with inspection rights, practical limitations exist—sponsors can refuse unreasonable requests, require advance notice, and limit inspection frequency preventing harassment. Exercise inspection rights judiciously: conduct reasonable reviews when performance concerns arise but avoid excessive demands creating adversarial relationships. If sponsors resist legitimate inspection requests regarding concerning performance issues, consider that a major red flag suggesting potential problems they’re hiding.

[IMAGE 2]

Critical Operating Agreement Provisions: Reading Between the Lines

Operating agreements govern every aspect of capital partners relationships—these legally binding contracts supersede default partnership laws, creating custom rules specific to each investment. Reading operating agreements thoroughly before investing isn’t optional caution but essential due diligence protecting your interests through identifying problematic provisions before committing capital.

Preferred return structures define how cash flow gets prioritized between limited and general partners. Strong provisions provide limited partners with true preferred returns—distributions flow 100% to LPs until they achieve target annual returns (8% for example), only then do general partners participate. Weaker structures provide “pari passu” distributions where LPs and GPs receive cash flow proportional to ownership from day one, with “preferred return” meaning only that underwriting assumes LP returns hit targets—not that distributions actually get prioritized. The distinction matters enormously: true preferred returns protect LP downside by ensuring you receive target returns before sponsors earn carried interest, while pari passu structures with assumed preferred returns provide no actual distribution priority. Scrutinize exact language—does it say LPs “shall receive” or “are projected to receive” preferred returns? The former creates enforceable rights while the latter merely states hopeful assumptions.

Waterfall specificity determines exactly how profits split between partners after preferred returns. Clear provisions specify: “After LPs receive 8% annual preferred returns on invested capital, additional distributions split 80% to LPs and 20% to GPs until LPs achieve 12% cumulative returns, with remaining distributions splitting 70/30 in favor of LPs.” Ambiguous provisions might state: “Distributions will be made in accordance with partnership interests and promote structures,” without defining exact splits or thresholds. Vague language creates opportunities for disputes or sponsor interpretation favoring their interests. Demand crystal-clear waterfall definitions with specific percentages, return thresholds, and calculation methodologies before investing.

Clawback provisions require general partners to return excess distributions if final returns prove lower than interim distributions suggested. Example: GPs receive quarterly promoted interests based on achieving LP preferred returns, but upon sale, final cumulative returns prove insufficient to have justified those promotes. Clawback provisions require GPs refunding excess distributions to LPs ensuring waterfalls get honored on cumulative basis, not just quarter-by-quarter. However, many operating agreements lack clawback provisions entirely, allowing GPs to keep interim distributions even when final results don’t justify them. Without clawbacks, sponsors might take aggressive distributions early in holds, then if deals ultimately underperform, LPs can’t recover excess GP distributions.

GP capital contribution requirements ensure sponsors have personal capital at risk alongside limited partners. Strong provisions mandate GPs invest meaningful amounts (5-20% of equity) subject to same terms as LPs—if deals fail, GPs lose money too, creating powerful alignment of interests. Weak provisions allow GP “contributions” through sweat equity only, or permit GP capital coming from acquisition fees or other partnership payments rather than true at-risk personal funds. Some agreements even allow GP contributions in form of loans to partnerships rather than equity, letting sponsors extract capital through loan repayments while LPs remain equity investors bearing losses. Verify GP capital represents true at-risk equity contributions, not creative accounting making sponsors appear invested when they’re not actually exposed to losses.

Fees and compensation transparency requires complete disclosure of all payments sponsors receive—acquisition fees, asset management fees, property management fees through affiliated entities, construction management fees on renovations, refinancing fees, disposition fees, and promote percentages. Legitimate fees compensate sponsors for real work but excessive fees or undisclosed payments to sponsor affiliates constitute self-dealing enriching sponsors at LP expense. Red flags include management contracts with sponsor-owned property management companies at above-market rates, construction contracts with sponsor construction affiliates billing premium prices, or lending arrangements where sponsors earn interest on loans to partnerships. Demand complete fee disclosure including all payments to sponsors or sponsor-controlled entities.

Conflict of interest provisions establish how partnerships handle situations where sponsors’ personal interests conflict with partnership interests. Strong provisions require conflicts being disclosed to limited partners with approval votes before proceeding. For example, if sponsors want to sell partnership property to another entity they control, they must disclose the conflict and obtain LP approval. Weak provisions might allow conflicts proceeding without disclosure or approval, or even explicitly permit conflicts stating that certain transactions don’t constitute conflicts requiring special handling. The absolute worst provisions eliminate fiduciary duties entirely, allowing sponsors acting in self-interest without obligation to prioritize partnership interests. Never invest in deals where operating agreements eliminate fiduciary duties or give blanket conflict approvals.

Amendment provisions specify how operating agreements can be modified after capital raise completes. Strong protections require supermajority LP approval (67-75%) for any material amendments, preventing sponsors unilaterally changing terms midstream. Dangerous provisions allow GP-only amendments or simple majority amendments, enabling sponsors to modify agreements favoring themselves after securing your capital. Even with amendment restrictions, definitions matter—what constitutes “material” versus “non-material” amendments? Broad GP authority to make “non-material” amendments creates loopholes for significant changes without LP consent. Insist on limited amendment authority requiring supermajority LP approval for all but administrative changes.

Indemnification clauses protect general partners from liability for partnership obligations, errors, or losses except in cases of fraud, willful misconduct, or gross negligence. These provisions are standard and reasonable—sponsors shouldn’t face personal liability for ordinary business decisions that don’t work out or for honest mistakes not rising to gross negligence. However, overly broad indemnification extending even to gross negligence or lowering standards to require proving “bad faith” rather than mere negligence create dangerous insulation from accountability. Review indemnification carefully: sponsors should be protected from ordinary business risk but remain liable for truly problematic conduct like fraud or reckless disregard for partnership interests.

[IMAGE 3]

Red Flags in Capital Partners Structures: When to Walk Away

Certain characteristics in capital partners opportunities signal problematic structures, inadequate protections, or questionable sponsor integrity—learning to recognize these red flags prevents capital commitment to deals likely causing losses, conflicts, or complete capital loss despite attractive projections.

Sponsor refusal to provide complete track records indicates either inexperience with full investment cycles (properties bought and sold demonstrating complete strategy execution) or track records containing failures they don’t want disclosed. Strong sponsors readily provide audited performance summaries showing historical deal results—purchase prices, hold periods, cumulative distributions, exit proceeds, and actual versus projected returns. Sponsors claiming proprietary concerns prevent disclosure, providing selective good examples without comprehensive history, or lacking any completed deals creating track records warrant extreme skepticism. Never invest with sponsors unwilling to thoroughly document their performance history.

Zero sponsor capital contribution creates complete misalignment—sponsors earning fees and promoted interests while risking none of their own money has no downside exposure if deals fail. This structure incentivizes volume over quality: raising capital, acquiring properties, collecting fees, then moving to next deal regardless of LP outcomes. Sponsors investing personal capital at risk alongside LPs face actual consequences if deals underperform—they lose money too, creating powerful motivation for careful underwriting and diligent management. Walk away from deals where sponsors contribute zero personal capital, especially when combined with high acquisition fees suggesting their motivation is fee collection rather than long-term partnership success.

Elimination of fiduciary duties in operating agreements removes legal obligations for sponsors to act in partnership’s best interests rather than their personal interests. While sponsors can include provisions modifying default fiduciary standards, completely eliminating these duties signals intent to prioritize personal interests over LP interests with legal authorization. Sponsors requiring fiduciary duty eliminations likely plan transactions or behaviors they know might not withstand fiduciary scrutiny. No legitimate sponsor needs fiduciary duties eliminated to operate effectively—these eliminations serve only to facilitate self-dealing or conflicts of interest. This red flag alone justifies walking away regardless of projected returns or sponsor reputation.

Excessive fees substantially above market norms—perhaps 5% acquisition fees instead of typical 1-3%, or 5% annual asset management fees instead of typical 1-2%—indicate sponsor focus on fee extraction rather than LP returns. High fees drain cash flow that should distribute to investors, reducing actual returns despite strong property performance. Calculate fee impact: if sponsors collect 5% acquisition fees, 4% annual fees, and 3% disposition fees on $10 million properties, they’re extracting $500,000 upfront, $400,000 annually, and $300,000+ at sale—potentially $2 million+ in fees over 5 years before any promote. These fee levels work only if properties perform exceptionally, but if sponsors focus primarily on fee collection, exceptional property performance becomes unlikely.

Vague financial projections lacking detailed assumptions or sensitivity analysis suggest sponsors haven’t conducted thorough underwriting or don’t want scrutiny of optimistic assumptions. Strong projections show line-by-line revenue and expense detail, clear assumption documentation, sensitivity analyses showing results under various scenarios, and conservative base cases generating adequate returns even without favorable assumptions. Vague projections presenting only best-case scenarios with minimal detail prevent verification of reasonableness. If you can’t verify assumption reasonableness because sponsors won’t provide detail, assume projections are unrealistic. Sophisticated sponsors welcome analytical investor questioning, while questionable operators resist scrutiny knowing their projections won’t withstand detailed examination.

Pressure to invest quickly with limited due diligence time signals sponsors prioritizing capital raising speed over investor informed decision-making. Legitimate opportunities allow adequate time reviewing operating agreements, analyzing financial projections, conducting sponsor background research, and consulting advisors. Sponsors claiming deals will “close immediately” without time for proper review often know scrutiny would reveal problems, hoping to secure capital before investors discover issues. Any sponsor unwilling to provide 7-14 days minimum for thorough due diligence prioritizes their timeline over your interests. Rushed investment decisions under time pressure frequently lead to regret—never let artificial urgency override comprehensive evaluation.

Lack of third-party verification for key information—property valuations, rent comps, expense estimates, or sponsor credentials—creates opportunities for material misrepresentations. Sponsors should provide third-party appraisals, market studies from reputable firms, audited financial statements for existing properties, and references from prior investors verifiable independently. Self-reported metrics without verification might be completely fabricated. Always verify sponsor track records through referenced prior investors (not just hand-selected testimonials), confirm property information through independent appraisals or broker opinions, and validate market data through third-party sources. If sponsors resist verification or claim everything is “proprietary,” assume they’re hiding unfavorable realities.

Sponsor financial instability or personal financial problems create risks they’ll misappropriate partnership funds or fail to support deals during difficulties. While obtaining complete sponsor financial disclosure proves difficult, certain public information reveals problems: previous bankruptcies, foreclosures, lawsuits from prior investors, liens against sponsor properties, or SEC sanctions. Conduct background research: search sponsors in court databases, review SEC records for enforcement actions, and search their names plus terms like “lawsuit,” “fraud,” or “complaint.” Any history of investor disputes, regulatory violations, or personal financial catastrophes indicates probable future similar problems. Financially unstable sponsors might misuse partnership funds addressing personal crises or simply lack resources supporting partnership needs during downturns.

[IMAGE 4]

What to Do When Capital Partners Relationships Deteriorate

Despite careful sponsor selection and thorough operating agreement review, capital partners relationships sometimes deteriorate through sponsor underperformance, conflicts of interest, communication breakdowns, or discovering fraud or misconduct after investing. Understanding your options when relationships sour helps you protect remaining capital and potentially recover losses when sponsors act inappropriately.

Communication attempts should precede escalation—many conflicts stem from misunderstandings or communication failures rather than intentional sponsor misconduct. Start by raising concerns directly with sponsors through email or scheduled calls, documenting concerns clearly and requesting specific information or actions addressing issues. Perhaps sponsors aren’t providing quarterly reports because of administrative disorganization rather than intentionally hiding problems. Maybe concerning decisions reflect strategic considerations you don’t fully understand rather than self-dealing. Give sponsors opportunities to address concerns professionally before assuming worst motives or escalating conflicts. Keep written records of all communications for future reference if conflicts intensify.

Other limited partner coordination multiplies influence when multiple LPs share concerns. Individual limited partners often hold 2-5% partnership interests—insufficient for controlling votes or forcing action alone. However, if 10-15 limited partners collectively representing 40-50% of LP interests organize around shared concerns, that coalition possesses significant power. Reach out to fellow limited partners sharing information about concerns, discussing whether others experienced similar issues, and potentially organizing collective action if warranted. Some operating agreements prohibit LP collaboration without GP approval, but generally you can communicate with fellow investors about shared concerns. Organized LP groups negotiating collectively with sponsors often achieve results individual investors can’t.

Formal written notices to sponsors documenting agreement violations, demanding specific remedial actions, and establishing timelines create records supporting potential legal action if sponsors don’t respond appropriately. These notices cite specific operating agreement provisions being violated, demand concrete corrective actions, and specify reasonable timeframes for compliance. Example: “Section 4.3 of the Operating Agreement requires quarterly financial reporting. We have received no reports for Q2 and Q3 2024. Please provide complete financial statements for these periods within 15 days.” Formal notices demonstrate you’re serious about enforcing rights and create documented evidence sponsors received clear notice of concerns and failed to address them appropriately if litigation becomes necessary.

Exercising voting rights on major decisions when operating agreements grant approval rights allows blocking problematic sponsor actions. If sponsors propose selling properties at values you believe are too low, refinancing terms you view as excessive, or other major decisions requiring LP approval, you can vote against these proposals. However, this option only exists if operating agreements grant LP approval rights over specific decisions and if you can organize sufficient LP votes to block proposals—perhaps 25-40% depending on voting thresholds. If agreements grant sponsors broad unilateral authority over all decisions, you have no voting rights to exercise regardless of sponsor actions.

Demanding sponsor removal under “for cause” provisions provides nuclear option when sponsors commit fraud, gross negligence, bankruptcy, criminal acts, or material operating agreement breaches. This dramatic step requires substantial evidence of removable conduct, organizing enough LP votes to meet removal thresholds (often 67-75% of LP interests), and potentially intensive legal proceedings if sponsors contest removal. Sponsors don’t exit gracefully—expect litigation consuming time and money even with strong cause for removal. Only pursue removal when situation is truly untenable and you’ve exhausted reasonable alternatives, understanding this path likely ends in courtroom battles regardless of merits.

Mediation or arbitration provisions in operating agreements often require attempting alternative dispute resolution before litigation. Many agreements mandate mediation—non-binding negotiation with neutral mediator facilitating settlement discussions—before either party can file lawsuits. Some require binding arbitration rather than court litigation for resolving disputes. These provisions aim to resolve conflicts efficiently outside expensive courtroom battles, though they also sometimes serve sponsor interests by forcing LPs into private dispute resolution rather than public court proceedings. If your operating agreement includes ADR provisions, you must comply before pursuing litigation or courts will dismiss premature lawsuits requiring ADR first.

Litigation represents the last resort when sponsors violate agreements seriously, commit fraud, breach fiduciary duties, or engage in self-dealing despite all attempted informal resolution. Partnership litigation is expensive (legal fees often exceeding $100,000), time-consuming (cases taking 2-5 years reaching resolution), uncertain (judges and juries can reach unexpected conclusions), and emotionally draining (relationships destroyed entirely). However, sometimes litigation proves necessary protecting substantial capital from sponsor misconduct. Before filing, consult experienced partnership litigation attorneys evaluating case strength, estimating costs and timelines, and analyzing probability of recovering damages sufficient to justify litigation expenses. If attorneys won’t take cases on contingency (receiving portions of recoveries rather than hourly fees), that signals weak cases unlikely to produce damages offsetting legal costs.

Selling LP interests provides exits from problematic partnerships if operating agreements permit transfers and you can find buyers. However, most partnerships restrict transfers, and even when permitted, selling distressed partnership interests typically requires accepting substantial discounts—perhaps 40-60% of fair value or even more if situation is truly dire. Some investors specializing in distressed LP interests purchase positions at deep discounts, providing liquidity but at prices reflecting substantial risk. Weigh immediate liquidity at discounted values against potentially better outcomes from attempting to resolve issues or waiting for property sales even if timelines extend. Sometimes cutting losses through discounted sales proves less costly than continued carrying costs and management headaches.

[IMAGE 5]

Protecting Yourself: Due Diligence Before Becoming Capital Partners

Preventing capital partners problems through thorough upfront due diligence proves far more effective than attempting to resolve conflicts after committing capital to poorly structured deals or problematic sponsors. These preventive steps reduce your exposure to bad partnerships dramatically.

Operating agreement review by experienced partnership attorneys protects you through professional evaluation of terms, identification of problematic provisions, and recommendations for negotiations before signing. Budget $1,500-$3,000 for attorney review of operating agreements and private placement memorandums—modest costs preventing much larger losses from committing capital under unfavorable terms you didn’t fully understand. Attorneys experienced in partnership structures identify concerning provisions you’d miss, explain implications of complex legal language, and advise whether specific deals provide adequate investor protections justifying capital commitment. Never invest substantial capital without legal review regardless of sponsor pressure claiming legal review is unnecessary.

Reference checks with prior limited partners provide unfiltered perspectives on actual sponsor performance versus marketing promises. Request contact information for 5-10 prior investors from previous deals—random selections, not sponsor-curated testimonials. Ask these references: Did sponsors deliver projected returns? How was communication quality and frequency? Did sponsors handle challenges appropriately? Did they act with integrity when conflicts arose? Would you invest with them again? Why or why not? Any concerning themes across multiple references—missed projections, poor communication, conflicts over fees, or refusals to reinvest—signal probable similar experiences with your investment. Strong sponsors readily provide numerous satisfied references, while problematic sponsors resist reference checks or provide only carefully selected cheerleaders.

Background research on sponsor companies and principals reveals litigation history, regulatory actions, bankruptcies, foreclosures, criminal records, or other public information suggesting problems. Search sponsors in federal and state court databases, SEC enforcement action listings, bankruptcy records, local property records, and general web searches for negative information. Look for patterns: one lawsuit from a disgruntled investor might reflect nothing, but five lawsuits from different investors across multiple deals indicates probable pattern of problems. Any regulatory sanctions from SEC, state securities regulators, or licensing boards merit serious scrutiny. Criminal records, personal bankruptcies, or prior business failures don’t necessarily disqualify sponsors but warrant detailed understanding of circumstances before entrusting them with your capital.

Financial projections independent verification prevents investing based on unrealistic assumptions or manipulation. Hire third-party firms reviewing financial models, validating market data, confirming comparable rent and sale comps, and providing independent opinion on projection reasonableness. These reviews cost $2,000-$5,000 but provide objective analysis uncovering overly optimistic assumptions or outright fabrications. While you likely lack expertise evaluating underwriting yourself, professionals experienced in market analysis identify aggressive assumptions, compare projections against market norms, and advise whether projected returns justify inherent risks. Never invest based solely on sponsor-provided numbers without independent verification ensuring basic reasonableness.

Start-small strategy invests modest amounts in first deals with new sponsors, reserving larger investments for proven performers after experiencing their actual operations, communication, and execution over complete cycles. Rather than investing $200,000 with an unknown sponsor on their attractive opportunity, consider $50,000 initial investment despite possibly lower returns due to smaller position size. After observing their performance—reporting quality, distribution timing, management competence—increase investment sizes in subsequent deals if they’ve proven trustworthy and competent. This cautious approach limits initial downside while providing experience evaluating actual performance versus promises. Some sponsors resist smaller investments preferring fewer larger LPs, but sponsors unwilling to work with appropriately cautious first-time investors should raise concerns about their flexibility and reasonableness.

Diversification across multiple sponsors, strategies, markets, and property types protects against single sponsor failure, market downturn, or strategy-specific challenges destroying concentrated positions. Rather than investing $500,000 with single sponsor, consider six $80,000 positions with different sponsors across various markets and approaches. This diversification smooths portfolio returns—if one sponsor underperforms or one market struggles, diversified portfolio maintains aggregate performance through successful positions offsetting disappointed ones. Building diversified portfolios requires time—perhaps 2-3 years accumulating 5-8 positions as appropriate opportunities arise. Resist urgency to deploy capital immediately into limited opportunities; patient disciplined diversification beats rushing into concentrated bets.

Understand your LP rights completely before signing, not hoping for best but preparing for worst—even with excellent sponsors, unexpected problems sometimes emerge requiring exercising rights protecting your interests. Know whether you possess voting rights, removal provisions, information access guarantees, and realistic exit options. Understand what constitutes major decisions requiring approval versus discretionary GP authority. Know capital call provisions—could you fund additional 20% if demanded? Read every operating agreement word thoroughly despite length and complexity, highlighting unclear provisions requiring explanation. Informed investors who understand exact rights and limitations protect themselves far better than those who invest based on trust and optimism hoping everything works out favorably.

Your Next Steps: Becoming Educated Capital Partners

Converting capital partners knowledge into protected investments requires systematic preparation ensuring you understand rights, evaluate sponsors thoroughly, and structure relationships maintaining appropriate safeguards before capital deployment in any partnership opportunity.

Educate yourself about partnership structures, securities regulations, and typical terms before evaluating specific opportunities. Read operating agreement samples (many sponsors post template agreements on websites) noting common provisions and varying approaches to GP/LP rights and responsibilities. Study SEC resources about private placement regulations understanding disclosure requirements, exemptions, and investor protections. Learn real estate partnership terminology—preferred returns, promoted interests, waterfall structures, catch-up provisions, clawback clauses—fluently before reviewing actual deals. This foundational education allows more effective opportunity evaluation compared to learning on the fly while sponsors pressure investment decisions.

Schedule a call discussing overall investment strategy balancing active property ownership through DSCR financing with passive capital partners positions. Many sophisticated investors maintain mixed portfolios—directly owning 3-5 properties they actively manage or oversee while simultaneously holding LP positions in 5-10 partnerships accessing markets, property types, or deal sizes they couldn’t access independently. This blended approach provides diversification, geographic reach, and risk spreading while maintaining some direct control over portions of portfolios.

Join investor networks and educational communities learning from other limited partners’ experiences. Many successful passive investors share insights through forums, podcasts, mastermind groups, or local investor associations. These connections expose you to red flags others encountered, introduce you to quality sponsors with proven track records, and provide support when navigating challenging situations with existing partnerships. Investor communities where members discuss actual deal experiences—good and bad—prove invaluable for realistic partnership education beyond sponsor marketing materials presenting only positive possibilities.

Build relationships with multiple sponsors over time rather than rushing into first opportunities discovered. Attend sponsors’ educational webinars, read their newsletters analyzing market trends, request one-on-one introductions discussing investment philosophies even without immediate opportunities available. This relationship building helps you evaluate sponsor competence, integrity, and communication quality before money pressures influence judgment. Sponsors appreciate educated investors who ask sophisticated questions, making initial contacts easier when relationships begin without transaction pressure. After knowing 5-6 sponsors well through extended relationship building, you can make more informed selections when deploying capital.

Review every opportunity skeptically regardless of sponsor reputation, projected returns, or investment pressure. Reputations sometimes deceive—famous sponsors occasionally stumble badly despite past success. Strong historical returns don’t guarantee future performance. Attractive projections often reflect aggressive assumptions rather than likely outcomes. Make every opportunity independently prove its merit through your analysis—sponsor track record, operating agreement terms, financial projection verification, and risk assessment matching your specific capital and objectives. Skeptical evaluation prevents enthusiasm or fear of missing out overriding rational analysis.

Maintain investment discipline focusing on risk management rather than return maximization. Target earning 14-18% returns with moderate risk rather than 25% returns with extreme risk likely resulting in capital loss. Pass on opportunities failing to provide adequate investor protections regardless of projected returns—bad structure with great returns often becomes bad structure with losses when problems arise. Invest only when comfortable with downside scenarios understanding worst-case outcomes beyond losing entire invested capital in bankruptcy. Calculate whether you can sustain partnership commitments through full hold periods—perhaps 5-7 years—without needing liquidity for other purposes.

Know when to walk away from opportunities regardless of pressure or attractiveness. If sponsors won’t provide adequate time for due diligence, refuse reference checks, won’t allow attorney review, or push signing before thorough understanding—walk away. If operating agreements eliminate fiduciary duties, provide no LP voting rights, lack sponsor capital contributions, or contain other problematic provisions—walk away. If intuition suggests something isn’t right despite inability to identify specific problems—walk away. Capital partners opportunities remain abundant; missing one to maintain appropriate caution preserves capital for better structures with protective terms and trustworthy sponsors.

Remember that as capital partners providing limited partner funding, you possess less control than active investors but theoretically should benefit from professional sponsor expertise managing properties better than you could independently. This trade-off—surrendering control for professional management—only works when sponsors actually possess superior expertise, act with integrity, and honor partnership agreements protecting your interests. Thorough upfront due diligence, clear operating agreement protections, and ongoing monitoring ensure capital partners relationships deliver expected passive income and wealth building rather than becoming expensive lessons about why investor protections matter.

Frequently Asked Questions

What percentage of profits should capital partners (limited partners) receive versus general partners?

Typical split after limited partners receive preferred returns ranges 70-80% to capital partners (LPs) and 20-30% to general partners (GPs) on remaining profits. Some deals use 80/20 splits until LPs reach certain cumulative return thresholds (perhaps 12-15%), then shift to 70/30 or 60/40 on additional profits rewarding GPs for exceptional performance. These percentages reflect that LPs provide 85-95% of capital while GPs provide sweat equity, with splits ensuring both parties receive compensation roughly proportional to their contributions—LPs for capital provision and GPs for operational execution. Be wary of splits favoring GPs excessively, like 50/50 or 60/40 in GP favor, unless sponsors contribute substantial capital proportional to their profit shares. Similarly, 90/10 splits in LP favor with minimal GP participation discourage quality sponsor performance since their upside proves limited even with excellent execution. Evaluate whether proposed splits adequately align everyone’s interests toward maximizing returns rather than disproportionately benefiting one party.

Can I get my money back if I change my mind after investing as limited partner?

Generally no—capital partners investments are binding commitments without cooling-off periods or refund rights after subscription documents are executed and capital is transferred. Once you invest as limited partner, your only exit options are holding until partnership terminates through property sale, selling your LP interest to another investor (if operating agreements permit transfers and you find buyers), or potentially negotiating buyouts with sponsors or other partners. Some deals offer limited redemption rights under hardship circumstances, but these are rare and typically come with substantial penalties like 20-30% discounts to fair values. Before investing, accept that capital remains locked up for full 3-7 year hold periods without liquidity except through distressed sales at substantial discounts. Never invest capital you might need before partnerships naturally terminate—emergency expenses, job loss, or investment opportunities don’t create exit rights from illiquid partnership investments. The binding nature of these commitments makes thorough upfront due diligence critical since walking away after committing capital proves difficult or impossible.

What happens to capital partners if general partners go bankrupt or die?

Operating agreements should address these scenarios through succession planning provisions, but outcomes vary dramatically based on specific terms. If GPs file bankruptcy, partnership interests might become bankruptcy estate assets subject to creditor claims, though limited partner interests typically remain protected as separate ownership. GP death typically triggers succession provisions: some agreements allow deceased GP estates appointing replacement operators, others require remaining GPs or LP supermajority voting to select successors, while some mandate partnership dissolution and property sales. Best-case scenarios involve smooth transitions where replacement general partners continue operations maintaining performance consistency. Worst cases force rushed property sales at unfavorable prices destroying projected returns when key sponsors become unavailable. Before investing, review succession provisions understanding exactly what happens if sponsors become unavailable. Strong provisions include detailed succession procedures, perhaps even identifying backup operators in advance, ensuring partnerships can continue functioning without devastating disruptions if original sponsors depart unexpectedly through death, disability, or other reasons.

How do capital partners get tax deductions from depreciation if we don’t actually own properties?

Limited partners receive proportional allocations of partnership tax items including depreciation deductions through pass-through taxation even though partnership entities hold legal title to properties, not individual LPs. The partnership files informational tax return (Form 1065) calculating total income, expenses, gains, losses, and deductions including property depreciation. Each partner receives K-1 forms showing their proportional shares of these items for inclusion on personal tax returns. Your 2% limited partner ownership receives 2% of depreciation deductions, 2% of income, 2% of expenses, etc. This creates tax benefits—receiving cash distributions might be offset entirely by depreciation deductions showing paper losses reducing taxable income even while receiving money. However, passive activity loss rules limit using passive losses to offset active income (wages, business income) unless you qualify as real estate professional or have other passive income to offset. Accumulated unused passive losses carry forward indefinitely, offsetting gains when properties eventually sell or when you generate sufficient passive income from multiple partnerships. Consult tax professionals understanding how partnership depreciation fits your specific tax situations maximizing available benefits.

Should capital partners ever accept zero voting rights on major decisions?

Some investments defensibly justify limited partner voting rights being minimal or nonexistent, particularly with institutional-quality sponsors having impeccable track records managing large portfolios for sophisticated investors who value operational efficiency over individual investor control. However, first-time investors or those working with less-established sponsors should generally insist on voting rights over fundamental decisions—property sales outside planned timing, refinancing materially, GP removal, and material operating agreement amendments. These rights provide ultimate protection when sponsors make problematic decisions or relationships deteriorate. Without voting rights, you’re completely passive investors hoping sponsors always act appropriately with no recourse when they don’t. The trade-off is operational efficiency (no delays obtaining LP votes on every significant decision) versus investor protection (ability blocking truly problematic actions). Evaluate whether specific sponsor track records, reputations, and structures justify surrendering voting rights, or whether maintaining those rights provides important safeguards warranting slightly reduced operational efficiency. For most investors, maintaining voting rights over major decisions represents prudent protection even with highly reputable sponsors—you’re not suspecting sponsor misconduct but simply ensuring appropriate recourse mechanisms exist if unexpected problems emerge.

Related Resources

Also helpful for passive investors:

- Invest in Apartment Complexes — Understanding commercial multifamily syndication structures

- Passive Income Real Estate Strategies — Multiple approaches to passive investing

- Real Estate Investment Risk Management — Protecting capital through portfolio construction

What’s next in your journey:

- Tax Strategies for Real Estate Investors — Maximizing after-tax returns from partnership investments

- Building Generational Wealth Through Real Estate — Long-term wealth building through passive positions

- Advanced Portfolio Diversification — Balancing active and passive real estate investments

Explore your financing options:

- DSCR Loan Program — Direct property ownership complement to passive investing

- Portfolio Loan Program — Multiple property financing for active portfolio

- Asset-Based Loan Program — Qualification based on financial strength

Need a Pre-Approval Letter—Fast?

Buying a home soon? Complete our short form and we’ll connect you with the best loan options for your target property and financial situation—fast.

- Only 2 minutes to complete

- Quick turnaround on pre-approval

- No credit score impact

Got a Few Questions First?

Let’s talk it through. Book a call and one of our friendly advisors will be in touch to guide you personally.

Schedule a CallNot Sure About Your Next Step?

Skip the guesswork. Take our quick Discovery Quiz to uncover your top financial priorities, so we can guide you toward the wealth-building strategies that fit your life.

- Takes just 5 minutes

- Tailored results based on your answers

- No credit check required

Related Posts

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get new posts and insights in your inbox.